Zooming in, zooming out: Q&A with SLAC’s Deputy Director for Science & Technology Alberto Salleo

A materials scientist who explores how plastic molecules can mimic the brain, Salleo sees strength in the big picture and minute details of the people, tools and partnerships at SLAC.

Key takeaways:

- Less than a year into his new role as SLAC’s deputy lab director for science and technology and chief research officer, Salleo is leaning into his penchant for making connections across the broad landscape of the lab’s research.

- He brings his own experience as a researcher, professor and department chair who uses the lab’s X-ray facilities to study materials that could be used in cutting-edge technologies.

- His vision for the lab includes integrating the tools and intellectual capital of its ecosystem to answer fundamental questions on many scales.

Since Alberto Salleo joined SLAC last March as the lab’s deputy director for science and technology and chief research officer, he has been purposefully oscillating between the lab and Stanford University.

In the early months, he was transitioning from his previous position as the chair of the university’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering in the School of Engineering, a position he had held since 2019. More recently, while continuing his work as a professor, he has become an advocate for deepening Stanford-SLAC research partnerships.

“I think of that relationship as a treasure trove full of intellectual connections and unique tools,” Salleo said.

We sat down with him recently to learn more about his background as a materials scientist; his talent for zooming in and out on problems to see both the big picture and the intricate details; and his thoughts about the future of SLAC science and technology.

How did you get interested in science & technology?

It’s the classic story of a kid getting a microscope as a present when he’s 10. I studied chemistry in Italy, where you choose your major early and stick with it. For five years it was all math, physics and chemistry. I started a doctorate in physical chemistry at the University of Rome and was awarded a one-year fellowship at the University of California, Berkeley, in the materials science department. That fellowship turned into a PhD, and 30 years later, I’m still here! I did my PhD research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The National Ignition Facility, NIF, was being built, and they wanted to understand why their high intensity lasers were damaging the lenses they used to focus the beam – that was my PhD project. After doing a postdoc on the topic of printed electronics at Xerox in Palo Alto, I joined Stanford as assistant professor in 2006, became a full professor in 2019 and a department chair shortly thereafter, which I did for six years until June 2025 when my job at SLAC fully ramped up.

What questions are you exploring now as a scientist?

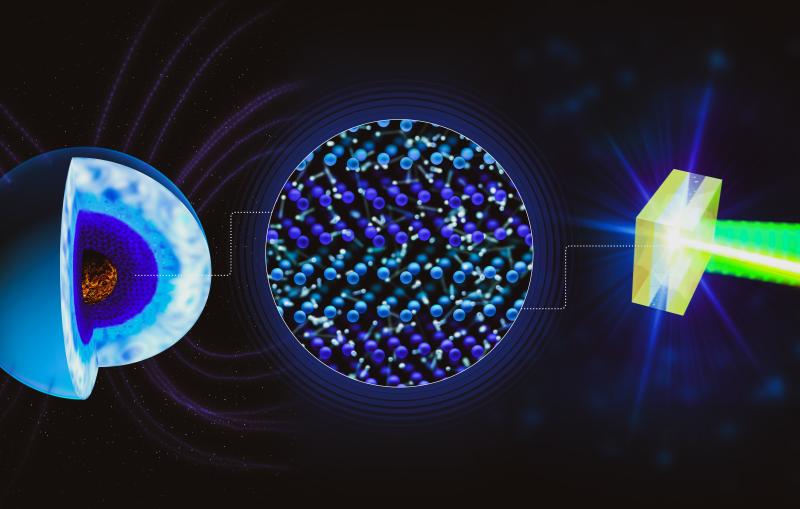

My group works on using polymer or plastic-like molecules in things that plastics aren’t known for. When you think of plastics, you think of static things like bottles. But the molecules we work with are active; they can emit light or transmit electricity. Plastics are easy to process compared to conventional electronic materials, and they are very flexible – you can imagine making electronic skins for robots, for example. We study fundamental questions about these materials, such as how their molecules are assembled and how they transmit electricity. These materials can also be tailored to sense particular chemicals. And lately we've also been working on using them to mimic how the brain works, making what are called artificial neurons, or artificial synapses. The brain is very efficient at computing, so can we get the same efficiency out of electronic devices that exhibit the same functionality as neurons and synapses? We use X-rays at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SSRL, to explore these questions.

So you’ve been using SLAC facilities for your science for some time?

Oh, yes, since I first started at Stanford. In fact, I just got a text from my students telling us when our next beamtime is at Beam Line 11.3. My very first summer as Stanford faculty, I was training a student on how to use the beamline. Now my students are very careful to keep me away from scientific instruments so that I won’t randomly push any buttons. [laughs] I remember when I was an undergrad and my advisor would come into the lab and push random buttons – just being a scientist!

What would you say is your science superpower?

I would say it’s two things: my attention to detail – being able to see things in the data – and connecting things that don’t seem connected at first. I can hold the big picture and zoom in and out. For example, I recently asked a student to send me two microscopic images of the same area taken under two different conditions, and I noticed a peculiarity of that image that tells us something about how these polymers are connected. So, I guess I could say that I still have that zooming-in ability, even though I don't have as much time to dedicate to it. Lately, I’ve been learning as much as I can about SLAC, visiting all the lab’s places, projects and people and absorbing as many details as I can.

What inspires you about SLAC science and technology?

All of it! I don’t have a background in cosmology, but I was fortunate to join SLAC just before the celebration of Rubin Observatory’s First Look, and how can you not be excited about Rubin science? The lab has an incredible breadth of science and technology, but one nice connecting thread is the vast amount of data we collect across the lab and the challenge of storing and processing that data. It's true for both Rubin and our light sources. And then there’s a unique culture at SLAC – the lab’s history and people – that permeates the place. I see how passionate people are about working here and the science they do. People are excited to come to work, and I’m excited to be here, too.

What directions do you see the lab going in? What are the main problems we can solve?

We are tackling many interesting problems at SLAC, from the origin of the universe to the behavior of atoms and molecules. One of my main tasks is to create an integrated science and technology strategy, and I see our potential to be the lab that brings an understanding of how a material works from the smallest, fastest scales – the motions of electrons – to the failure of the device. If we can integrate across our tools and people at the lab and university, we can explore fundamental questions about materials from very fast to human time scales and from very small to human length scales. I think we could be the only lab in the world that can do that because very few universities and national labs have that combination of tools, like our light sources, and people who study questions ranging from fundamental science to application-based engineering. And, of course, we are in a broader ecosystem of national labs and innovators in the Bay Area. I tell my students to look at a map – within a two-hour drive you can find a world-leading expert on any topic. The key is to integrate all that and get researchers the tools they need to answer any fundamental question.

We are hearing a lot about how AI is poised to revolutionize society. Do you see a role for SLAC in that?

AI permeates everything at the lab. We're probably producing the largest amount of data of any national lab, if you combine Rubin Observatory and the Linac Coherent Light Source, LCLS. And that’s a unique opportunity for us to lead in the AI-for-science space. We're not a leading computing lab per se, but we're an experimental lab that produces unique data sets that can be used to train AI and to figure out how to automate experiments. That's a huge opportunity for us and makes us pretty unique. AI models developed for science can also drive advances in technologies such as fusion and quantum computing.

As deputy for science and technology and CRO, what does your team look like? Are there any focus areas that stand out to you?

I’m bringing together several areas, such as strategic planning, tech transfer and strategic partnerships, and research security. Another focus is career development – early career programs, but also a pipeline of programs to support people throughout their careers with mentorship and training. I’d like to create something similar to the Stanford system of transitioning postdocs to career roles but tailored to the national lab environment. There are lots of opportunities to support individual contributors in becoming leaders and managers. I’d also like to strengthen and grow our partnerships with the DOE and Stanford by advocating for the value of those connections. I have benefited from them in my own work on campus and at SSRL, so I can speak to the potential of those relationships.

SSRL and LCLS are DOE Office of Science user facilities. NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory is a joint initiative of the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science (DOE/SC).

For media inquiries, please contact media@slac.stanford.edu. For other questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.